Have you ever turned to an algorithm to get feedback on a suspicious rash or uploaded blood work results for an interpretation? Many of us are already using LLMs like ChatGPT to ask questions about our health or even explore potential diagnoses when physicians haven’t been able to provide speedy or accurate answers. A national survey found that nearly six in ten Americans consider AI-generated health information useful and reliable. Meanwhile, physicians are rapidly adopting the technology too, with two-thirds of U.S. doctors now using AI, up 78% since 2023.

AI is already widely used in administrative functions, replacing both front-office and back-office tasks. What is also inevitable is that AI will increasingly participate in direct care delivery — the structured workup, triage, screening, diagnosis, and eventually treatment. That shift is already underway. Companies like Akido Labs, Doctronic and General Medicine are using AI to drive efficiency for providers throughout the encounter. In Akido’s case, the company has its own provider network, so it leans on the AI for tasks like the potential diagnosis that its physicians review. On Tuesday of this week, Doctronic, which is also primarily human in the loop, announced that it is piloting a program with the state of Utah that leverages AI to renew a subset of medical prescriptions without a human involved.

Announcements like these may seem like science fiction. But the evidence is stacking up in favor of AI for care delivery, not just administrative tasks. Stanford Medicine recently published findings showing that an AI chatbot outperformed physicians who only had traditional clinical references — and that doctors paired with AI performed as well as the AI alone. Meanwhile, Microsoft’s “medical superintelligence” research suggests AI systems may achieve dramatically superior diagnostic accuracy compared to clinicians in certain scenarios and even recommend more cost-effective treatments.

Medical experts have also stressed that solutions like these are needed, given global shortages when it comes to medical treatment.

“We are feeling the squeeze,” said Thomas Jackiewicz, president of the University of Chicago Health System, referring to the growing needs of our aging population and the current provider shortages across nursing, physicians, behavioral health providers, and more. “Technology can solve both the cost and access problem.”

But a frictionless future where humans and AI both practice symbiotically won’t happen overnight. Legal, cultural, structural, and financial barriers must still be overcome. Some doctors are getting backlash from their peers for using AI; Johns Hopkins research found that physicians who rely on AI are often viewed as less competent by colleagues. Emerging concerns also persist about “deskilling,” where doctors may lose proficiency if over-reliant on technology — a fear highlighted by reporting on AI’s impact on medical competence. And a lawsuit filed in the San Diego Superior Court claims Sharp Healthcare recorded doctor-patient conversations using Abridge without consent. The suit alleges that Abridge’s note-taking AI also added in statements that weren’t correct into the patient’s chart, including that they consented to the recording.

Many questions abound when it comes to liability. If AI makes a mistake and a patient gets hurt, is the physician who approved the algorithm’s decision responsible? The institution that contracted with the AI company? The AI company? Every legal expert I’ve spoken to says there are no definitive answers yet, and the inevitable lawsuits in the years to come will set important precedents for our industry. Entrepreneurs are finding that even despite these complexities, there is a clear path forward.

According to Jared Goodner from Akido Labs, which is building a health system that incorporates AI from the ground up:

“There’s absolutely low-hanging fruit here where you see the overlap between the clinical research, the cultural readiness, low liability, high patient safety, and a potential billing mechanism.”

We Are Entering the Training-Wheels Era

The goal of this piece is to examine the extent to which “autonomous” AI will change care delivery — and how quickly. My prediction after talking to dozens of experts, including doctors, operators, entrepreneurs, and lawyers? The near-term future is hybrid. Think of it like the development of autonomous vehicles. We are entering into what I call the “training wheels” era.

AI will be fully autonomous only in narrow, low-risk scopes initially, and we’ll start to see more of these in 2026. To offer one example, AI already outperforms trained ophthalmologists in detecting diabetic retinopathy, and because this specialty is severely under-resourced — particularly in rural settings — it is a plausible path to expand access. It helps enormously that a billing code already exists for autonomous retinal screening (CPT 92229), meaning reimbursement is clearer than in other areas. Companies like Microsoft, with big goals to bring more AI into healthcare, have already moved into this space.

Screening, diagnostics, and basic workflows will lead. And treatment, which is far more complicated, will follow from there. Imagine that an AI physician diagnoses a patient with pinkeye. Would the AI immediately send over a prescription? Or refer the patient to another AI — potentially one trained by specialists? Or would it loop them in with a human for a verification and/or second opinion? And how would payment work for all of these scenarios? Would this AI doctor have the same licensure and credentials as a human physician?

A reminder on upcoming webinars: |

Webinar Topic | Timing | Registration |

|---|---|---|

Unpacking the Data on the Telehealth Visits Patients Flocked to This Year | Jan 28, 2026 12 PM ET / 3 PM PT | Anyone can sign up here |

Breaking Point: How Soaring Healthcare Costs are Reshaping Employer Strategies | Feb 9, 2026 11 AM ET / 2 PM PT | Subscribers can sign up here |

Second Opinion x TytoCare: Unpacking CMS' $50B Investment into Rural Healthcare | Feb 5, 2026 12 PM ET / 3 PM PT | Anyone can sign up here |

Most of the companies I talked to are deploying with different strategies as they seek to answer these questions. There are no perfect answers nor a clear right and wrong. The key is to be creative and collaborative, and potentially also to follow models that already exist in other areas of medicine. Rebecca Mitchell, a physician and investor with Scrub Capital, notes that there are already ways in which non-physicians care for patients autonomously. So there may be ways that AI can slot into a care team, performing tasks more safely than a human. Whether seamless or complex, what’s clear is that the first players in the category will shape the next phase of care delivery, advancing us to a future where medical treatment moves from being a scarce resource to far more abundant.

Safety and Accuracy First

Patient safety sits at the center of everything. We’ve all heard the stories of AI confidently inventing plausible-sounding but fake answers. That’s terrifying when dealing with diagnoses, risk assessment, or even false reassurance. Part of the issue is structural — how these models are trained by human developers. Part of it is developmental. A leading academic researcher jokingly once labeled AI at a conference I attended last year as a “squealing infant.” Yale’s Dr. Harlan Krumholz recently told Second Opinion that we’re probably past infancy but still in a very “early adolescent” phase.

As an aside, when I asked ChatGPT whether it still considers itself a baby, it replied that it prefers the description that it is “an extremely capable specialist savant with big blind spots.” Honestly, that sounds like a lot of doctors I know.

Blind spots mean mistakes. And without guardrails, things can go very wrong, very fast.

And trust will not come overnight. Prashant Samant, CEO of Akido Labs, which uses AI directly in the clinical workflow to draft the differential diagnosis, noted that there needs to be “good governance of the AI engine itself.”

Ali Khokhar from Amigo.AI, a company in the patient safety space, has argued that healthcare should follow the blueprint of the most successful autonomous vehicle efforts like Waymo — slow, methodical rollout; simulation; rigorous validation; and broad-based training. To get there, we’ll need buy-in from patient advocacy groups, physician and nurse lobbies, technology vendors, hospitals, and other key stakeholders.

We’ll also need data exchange between systems. Healthcare hasn’t historically prioritized exchanging data and open APIs in favor of walled gardens. But in order for policymakers, regulators, and patient safety groups to gain confidence in AI’s role in care delivery, health data interoperability won’t just be a ‘nice to have.’ It’ll be a requirement. This is a classic chicken-and-egg problem. To prove that AI is safe and effective, we’ll need the data. But without the safety and efficacy, systems may be less comfortable moving to interoperability. There’s a reason that one of the first movers in this space- Akido Labs - has opted to become a healthcare system itself, caring for large patient populations, versus selling into them as a vendor.

The company says its full-stack approach means it is able to study the rollout of AI in diagnosis as part of the system, doing reinforcement learning and training its AI on its own large set of clean data (10M+ case studies). Akido describes this as a “living lab to test AI diagnosis both in existing healthcare infrastructure and beyond – bringing safety net care to Street Medicine programs in California.”

Are any other companies using the same strategy of building a healthcare system and employing the care professionals? If so, we’d love to hear from you.

The Question of Autonomy

Every AI care delivery company is wrestling with the same fundamental questions: How autonomous should AI be? And what meets the definition of autonomy? Technically speaking, true autonomy implies self-governance. If humans are always required to approve decisions — even in a perfunctory, box-ticking way — could the technology be described as truly autonomous? Or is it something else? Is there such a thing as partial autonomy?

Some experts I have been speaking with feel the issue is fairly clear-cut. “Either the product meets the definition of a regulated medical device — in which case it must be regulated — or it does not,” Jared Augenstein, a senior managing partner with Manatt, told me. However, he noted that the FDA’s interpretation of what meets the definition of a medical device can evolve over time. That’s created "significant confusion” in the marketplace, especially for novel types of devices using generative AI, he said.

Indeed, regulators are far more concerned about AI acting on its own to make decisions that impact patient health. The crux for regulators is whether the algorithm is making suggestions or making decisions. If a clinician remains in the loop and has to accept or reject a set of recommendations, the perceived risk is lower. This influences whether AI qualifies as:

Software as a medical device (SaMD), OR

Clinical decision support software (CDS)

Those distinctions matter enormously for oversight, product development, and more. There's a grey area here -- so for entrepreneurs unsure about which category their software falls into, the FDA published a website that suggests a series of questions. Depending on the responses, the agency indicates whether a product or service would have enforcement discretion or not.

At a high level, companies have two strategic paths:

Autonomous AI

Human-in-the-loop AI

Some companies will do both simultaneously, starting with humans to ensure they remain CDS and migrating toward autonomy in specific use-cases. That might also include piloting autonomy in tightly constrained contexts or geographies, but operating the vast majority of the business as a clinical decision support tool.

Companies like Akido Labs and General Medicine, both backed by healthcare investors, are demonstrating how companies can use AI to make care delivery more efficient, without moving down the regulated path. These companies are building patient-facing systems where AI gathers health data, responds using evidence-based resources like CDC guidance, and manages intake and workflow logistics.

In the case of General Medicine, patients get an AI consult first, followed by a human clinician within 24–48 hours. The AI isn’t billed. It’s infrastructure. Privacy law still applies because the company itself is a care provider.

Akido Labs is focused on using AI to solve the problem of specialty care visit capacity. The initial focus is on cardiology, given that many patients are waiting months to get an appointment. Per the company’s founders, Prashant Samant and Jared Goodner, a typical cardiology visit would involve a structured intake process and a set of targeted questions from a physician to a patient. From there, the doctor could detect red flags and then work up a differential diagnosis. Most human cardiologists do 10 to 15 of these sorts of visits in a day due to physical space and time constraints.

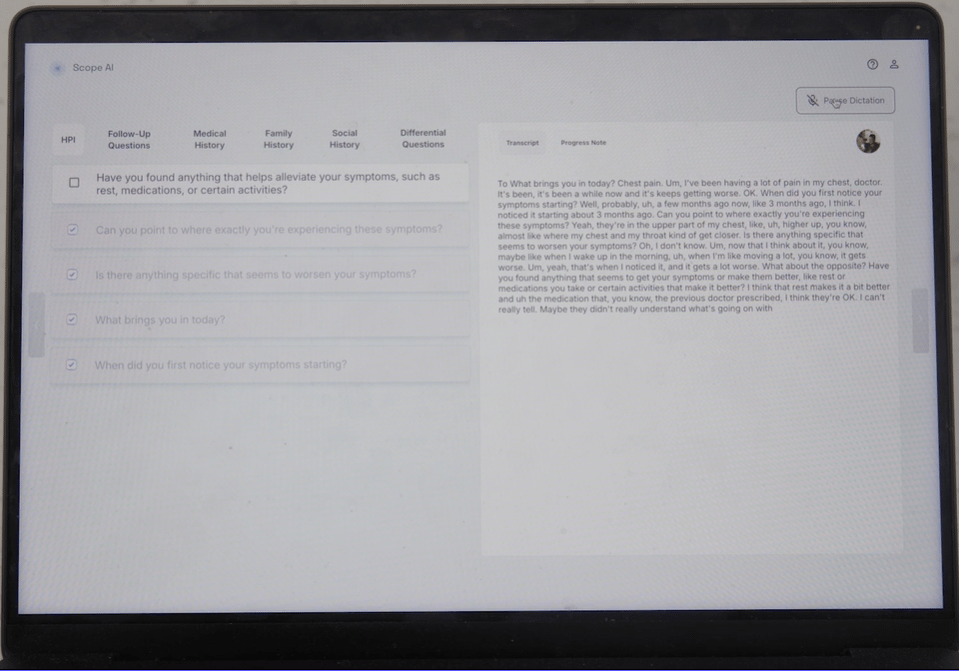

With Akido’s Scope AI tool, the AI assists with the intake, the questioning, the red flag detection, and so on - all the way through to identifying the likely orders and next steps. The physician gets an organized synthesis and can oversee the encounter. Per Akido, that means human ambulatory cardiologists can see 2.5x the normal number of patients in a brick-and-mortar setting. Overall, though, the volume of visits that an AI-assisted physician could take in a day could be as high as 10x, depending on the visit type.

These approaches also mean that doctors can spend more time with the patients who are most in need and might have the most complex issues.

There are also questions here related to how humans should be maintained in the loop. Jackiewicz from the University of Chicago Medicine believes the ideal opportunity is for AI to handle cases that do not need to be reviewed by a human for safety and accuracy. That leaves human experts with more time for the complex cases. Take radiology, for instance. There’s a huge shortage of radiologists, so we should be asking how to make the best use of the ones we do have while keeping patients safe. So could residents be trained differently to manage the cases that need to be seen, while the AI triages those that do not? Jackiewicz notes that in this scenario, we could significantly bring down costs and improve access. But we would have to get comfortable with a modicum of risk. Could we tolerate the 1 in 100,000 missed by the AI that should have been seen? Or to put it in a different way: Could we tolerate an AI that had better diagnostic abilities than a human but was still imperfect?

“Humans are also not perfect,” he said. “But we have this view that AI does need to be.”

The Regulated Path

Let’s move on to the second path: Software as a medical device. If the AI becomes a regulated medical device capable of autonomous clinical decision-making, it must go through FDA clearance. That introduces benefits — legitimacy, credibility — but also burdens: The model must be “locked,” iteration slows, and compliance obligations increase. And after all that, there might not be a viable path to get paid.

Those who have been in the space for a while may recall that the FDA once explored a more creative pathway with its “Pre-Cert Program” that sought to certify innovative companies rather than individual products. Ultimately, it couldn’t be implemented under the current law because the program didn’t work with existing regulatory structures. But it remains a blueprint for future modernization.

Meanwhile, regulatory gray areas continue to evolve in real time. I’ve been fascinated to watch the rise of mental health chatbots, where regulators face the tough task of distinguishing between wellness tools and medical treatment. Many companies in this space will argue that they’re supporting people with emotional resilience and mental wellness, versus treating diagnosed conditions like depression and anxiety. But where does that line get drawn? What happens if a patient starts asking the algorithm for more serious help? In the best case scenario, the handoff to a mental health provider would be challenging to execute in practice. Worst case, the algorithm could provide bad advice to an individual in harm’s way.

Another recent example that stirred up controversy was the Whoop blood pressure insights case, where lifestyle positioning was rejected by regulators because blood pressure is “inherently” clinical. It shows how tight this line can be. The FDA ultimately sent Whoop a warning letter, claiming that it breached the boundary of medical claims because measuring blood pressure (even trend lines) is associated with conditions like hypertension and hypotension.

Most companies today will operate under Clinical Decision Support (CDS) carve-outs where AI advises but doesn’t independently dictate. It allows faster iteration, which is preferable for most software companies. It allows testing. And it ultimately avoids device regulation…for now.

It’s worth pausing to consider what might happen when doctors follow AI recommendations 99.9% of the time. Perhaps patients might even prefer it. We can agree that most of us would not board a commercial flight that lacked a sophisticated autopilot that had been trained through millions of possible simulations. The same may be true for medicine.

Samant from Akido Labs thinks that the role of the physician won’t go away because of automation, but it will dramatically change. To borrow a military analogy, rather than a “Infantry,” the human physician is more of a “Field Marshal,” capable of meeting the needs of a population, including those with complex medical and psychosocial concerns. The idea is that AI can be a “force multiplier,” the company said, so that doctors can manage multiple teams and levels of complexity across a much greater area. Don’t think of the doctor of the future as a notary ticking boxes and signing off on paperwork.

“We aren’t replacing jobs at the title level in medicine anytime soon,” added Mitchell from Scrub Capital. “Doctors are still ultimately looked to for trust and safety, whether AI is part of the model or not, both by patients and by regulators.”

What is changing, per Mitchell, is what the job description says under the title, especially in startups with the luxury of redesigning care from scratch.

This may be a philosophical question. Soon, it will be a regulatory one.

Bottom line: The current regulatory schema doesn’t work in a world of AI. It was designed for narrow-use tools, not a technology that evolves as quickly as AI.

Where This Is Likely Going

I believe most companies will land in a “99% future.” Humans will remain involved for safety, empathy, trust, and liability.

For years, self-driving cars ran with safety drivers, even when they were technically capable of handling most environments autonomously. Medicine, with all its complexity and human nuances, will take even longer.

Some states are already experimenting with a future where very low-risk medical practices can be handled autonomously using AI. Utah, for instance, has launched an innovation sandbox, allowing companies to temporarily operate under alternative regulatory conditions. Federal proposals, like Senator Ted Cruz’s call for a national innovation sandbox, are early signs of similar thinking at a broader stage, although there will need to be more thinking around how these state-by-state experiments dovetail with corporate practice of medicine laws and other regulations.

Where autonomous AI adoption is most likely first: |

|---|

Use cases with strong evidence |

Clearly defined risk boundaries |

Existing reimbursement pathways (inclusive of billing codes) |

Diabetic retinopathy screening is the canonical example; Microsoft is already piloting remote ophthalmology solutions. Behavioral health chatbots will be fascinating to watch. So will wearables, which desperately want to provide deeper clinical insights, but are bumping hard into regulatory limits.

Getting Paid

Let’s imagine that the AI works brilliantly, doctors trust it, and regulators have blessed it. Someone still has to pay for it.

Many of today’s autonomous AI tools are diagnostics and obtain private laboratory CPT PLA codes. But beyond that, payment is sparse. As we have learned the hard way in digital health, FDA clearance does not equal reimbursement. This was a particularly painful lesson for many investors and founders in the digital therapeutics category.

Meanwhile, companies like Abridge and Nuance are proving that AI’s economic value may initially come from revenue generation— by helping doctors to document better and bill more — rather than the AI itself being reimbursed. There are examples of health systems offering these tools in exchange for physicians adding one more patient visit per day. Some tools that provide support for diagnosis and treatment will get paid for directly by payors, and others will not. But there will also be administrative tools that physicians pay for because they increase revenue or productivity and/or decrease costs.

Policy thinkers like Manatt’s Jared Augenstein are watching proposals like the ACCESS Model, which would open up performance or outcomes-based reimbursement in chronic disease management. This means that if patients’ core health metrics improve (say, a lowered A1C level), the AI algorithm — or rather, the company that built it — gets paid. But ACCESS focuses more on chronic condition management.

So companies today are pursuing six pragmatic strategies:

Consumer-pay models (typically an out-of-pocket subscription fee that includes the use of AI, and potentially wearables, along with human care providers)

Traditional fee-for-service with AI as backend infrastructure (the physicians can bill, but the AI is free and working in the background)

Risk-based contracts and capitation (where AI improves efficiency and outcomes for a patient population)

Supplier/vendor models (lots of companies already do this when selling into the employer channel, and it’s currently getting tested out in Medicare)

Employer contracts are paid per member per month (PMPM) and also leverage AI for margins.

CPT codes for direct reimbursement for payers (these are limited still, but there will be more)

Most likely, employers are the channel that will drive a lot of near-term adoption.

For now, AI itself rarely “bills” as a doctor. There is no licensure framework for AI clinicians.

But that will change. CPT billing was built for human labor, whereas healthcare’s next reality may require codes built for machines. There’s an ongoing industry debate about whether AI should have its own “modifiers,” similar to those that can be appended to telehealth services. Many of the experts I spoke to felt something like that might seem like a good idea in theory, but made little sense in practice. To that end, the American Medical Association recently convened a Digital Medicine Coding Committee. Currently, most companies that get FDA cleared for autonomous care delivery are in diagnostics, which do have specific CPT PLA codes. There are very few payable CPT codes beyond that.

The Bottom Line

Fully autonomous care delivery will happen. But gradually, carefully, and unevenly. Most of the industry will live in the 99% world — where AI does almost everything, but humans remain essential and practicing to the top of their license. Regulators will likely draw the hardest line between 99% and 100%.

As Augenstein told me:

“The difference between 99% and 100% may seem small. But from a regulatory and reimbursement standpoint, it’s enormous.”

And that future is arriving faster than most people realize.

Editors’ Note: Akido Labs is the sponsor for this piece, enabling us to make this piece available for free to our community.

Want to support Second Opinion?

🌟 Leave a review for the Second Opinion Podcast

📧 Share this email with other friends in the healthcare space!

💵 Become a paid subscriber!

📢 Become a sponsor