Special thanks to our friends at Headspace, who have made this post free to all users as part of sponsoring Second Opinion.

Headspace is an everyday mental health companion, offering AI-powered guidance, meditation, coaching, therapy and more through its all-in-one app. The company partners with employers and health plans to bring personalized support to millions.

Behavioral health has been through its own hype cycle over the past decade. The industry has made enormous progress in helping millions of people access the care they need, and yet it’s far from a solved problem. So why is it attracting so little funding compared to the heady days of the pandemic?

Behavioral health tech attracted meager investment for decades, in large part because it was hard for providers and clinics to get reimbursed. That all changed during the pandemic when it became the hottest category in digital health in 2020 and 2021. Investor enthusiasm was buoyed by policy changes that bolstered access to telemedicine, and the fact that payers seemed more amenable to paying out better, out-of-network rates for behavioral health treatment. There had also been a few exits that generated strong returns, such as Optum’s acquisition of AbleTo, which represented a big success story for the category. In 2021, per Galen Growth, investors poured $7.4 billion into behavioral health startups, up from $3.5 billion in 2020.

A lot has changed since then. In 2024, the space attracted just $1.3 billion in investment, and my hunch is that 2025 will be worse, unless we see a few more growth-stage deals getting done. So it’s fair to say that behavioral health investment has plateaued. There’s still capital moving in, but it’s far more challenging for companies to raise than ever before, particularly at middling rounds between early-stage venture and growth, like the Series B. Echoing trends we’re seeing across the industry, the startups that incorporate AI into their offerings are attracting the lion’s share of dollars. One recent example is Slingshot AI, which raised $93 million for its behavioral health chatbot “Ash.”

And yet, despite all the efforts to use technology to bolster access to mental health services, none of the clinical experts I spoke to for this piece think we’re much closer to solving the core problems. 160 million Americans still live in areas with behavioral health shortages and are struggling to access care. Only about half of the people with a diagnosed condition are getting treatment, as we continue to face a massive workforce shortage of mental health professionals. This crisis is particularly profound in younger generations. There’s been a rise in anxiety and depression, as well as an increase in suicide attempts and deaths, in the years since the pandemic. People with severe mental illness are still facing huge waitlists, waiting months if not years to get help. Lower-income patients are struggling the most. Studies have found that the majority of psychiatrists accepting new patients appear to favor commercially insured patients, with only 43% accepting those with Medicaid coverage and 60% accepting Medicare. A big reason for that is the lack of reimbursement, meaning that mental health professionals are paid better by patients with private insurance or by those who are willing to pay out-of-pocket.

Another challenge that is not often discussed in our industry: An oversupply of patients with means who can pay for therapy out-of-pocket, but may not need it. Not everyone needs to be seen by a clinical professional without a clear end date, either paying cash or through their health plan, while those who have a clinical-level problem often can’t afford it or get stuck on a waitlist. “That could be a way to increase (reimbursement) rates,” said Trip Hofer, CEO of Redox, an interoperability company, and the former CEO of behavioral health company AbleTo. Hofer explained that payers perceive behavioral health as a high utilization category, and there are challenges in determining the exact ROI. Without a universal standard of measurement, it's hard to determine that the intervention made the difference, versus say any other variable (going to the gym, starting a new diet, new medication, or whatever else). He believes companies that can find ways to differentiate between those who need clinical-level care and those who do not will have an edge in the market today. Those who do not need clinical-level care can still access sub-clinical support, such as coaching, peer counseling, AI-chatbots, and more.

Behavioral health company Headspace’s new CEO Tom Pickett agrees with this assessment, noting on a call with me that most behavioral health companies in the market today emphasize giving people access to more therapy. Very few companies are working to figure out who actually needs it. “A lot of people are using therapy who should not be using it,” he said. For those who do not, Pickett is in talks with health plans about the need to roll out more scalable, digital-first interventions, particularly those that leverage AI. It might also unlock more scalable business models, because reimbursement for therapy remains low compared to physical health, meaning that many companies struggle to sustain healthy margins as they grow.

A capital crunch after the 'obvious' bets have been made

Technology may represent a big unlock, but capital remains extremely challenging to access in this market. That’s because many venture capital and private equity firms have already made a bet in the space and are still waiting and watching to see if it’ll be a fund returner. In their minds, they’ve ticked the box on behavioral health and can move on to the next thing within health-tech, or outside of the sector altogether. These firms may also be conflicted out of making another investment in a competing company or business model, as there are only so many bets a single firm can make in behavioral health. This is having an impact on founders because venture remains the primary mechanism for them to raise capital for solutions that are built for scale.

Another challenge? Private equity and venture capital firms may need to see more exits in the category to justify further investment. Despite rumors for years that companies like Lyra Health and Spring Health are waiting in the wings, there’s been a dearth of IPOs. As a result, investors like Saurabh Bhansali, a partner at Health Velocity Capital, are expecting to see some consolidation in the category. He told me that might include mergers and acquisitions involving behavioral health companies, like Lyra’s recent buy-up of pediatric-focused Bend Health, or larger digital health companies purchasing solutions to be more comprehensive. One example: I wouldn’t be surprised to see Hinge Health making a purchase in the space, particularly as its competitor Sword just released its own mental health offering. As several friends in private equity noted to me, payers don’t seem to be as active as they may have been in the past in exploring acquisition opportunities in behavioral health. The big factors include antitrust, concerns about high utilization in behavioral health, and the lack of highly profitable businesses that are also growing at a solid clip.

Exits are important. Not only do exits bolster enthusiasm in the category, they also lead to so-called alumni networks that can catalyze the next generation of companies. Those who made money through an exit can afford to do a startup (not everyone can pay themselves below market for years), and they have the access to talent, the network, and the lessons learned to tackle the category and win. Take Oscar Health as a good example in the venture-backed health plan space. Since the company went public in 2021, more than a dozen of its employees have spun out to create new companies that are tackling different aspects of insurance. And they’re applying lessons they learned from the trenches while in operator mode. I’d argue behavioral health needs those kinds of seasoned entrepreneurs and operators to enter into the category, who will avoid making the same mistakes their predecessors did.

The firms still making investments tend to be the “die-hards” that are genuinely committed to the category. That level of conviction is required in this market, because the companies that are seeking funding now are looking at more niche areas within the category, tackling complex populations, or building totally new technologies that haven’t been seen before. “All the obvious deals have been done,” said Julia Bernstein, the chief operating officer of Brightside Health, a fast-growing company in the space that connects patients with behavioral health services, including psychiatrists. “There are a lot of firms that have a company in the portfolio that is taking care of mild to moderate behavioral health patients, providing care both synchronously and asynchronously.”

A reminder on upcoming webinars:

Webinar Topic | Timing | Registration |

|---|---|---|

Epic’s UGM: All the news, unpacked and how it will affect the rest of the healthcare industry. | Aug 22 | Anyone can sign up here |

Employers vs. Rising Healthcare Costs: Strategies for Employers to Cut Costs Without Cutting Care | Sept 4 | Anyone can sign up here |

The future of media: Operating in a world of independent journalism (in partnership with Hospitalogy) | Sept 8 | Paid subscribers can sign up here |

Obvious doesn’t mean bad. In fact, the obvious deals tend to be the big winners. Several of the companies that sell into the employer market as an EAP replacement will likely IPO in the next few years. But these corners of the market are saturated, making it harder for any new entrant. Venture-backed companies like Lyra Health, Spring Health, and Headspace were some of the first to attract venture dollars to pursue relationships with large health plans and employers, and some of these companies are now generating hundreds of millions in revenues. These companies will likely double down on more M&A in the coming years to fill in the gaps in their offerings.

Another so-called “obvious” opportunity that’s yielded strong companies is building networks of therapists willing to accept insurance, and providing them with the tools they need to succeed. Companies in this space, like Grow Therapy, Headway, and Alma, are performing well, and it’ll be fascinating to watch what happens in the coming years as health plans face cost pressures. UnitedHealthcare is the latest to report skyrocketing rates of behavioral health utilization in its corporate earnings.

Pediatric and youth behavioral health have also attracted a lot of venture capital dollars, even as the shortage of providers is becoming more pronounced (mental health professionals aren’t paid more to treat kids, but liability is higher). That category includes companies like Little Otter, Charlie Health, Brightline, Clarity Pediatrics, and more. Several of these companies have moved into treating kids with more severe mental illness by providing virtual intensive outpatient programs (IOPs). For those that do need therapy, as well as medication, there are companies making it easier to access psychologists and psychiatrists using their insurance, such as Brightside.

Where the next opportunities lie

There are plenty of strong bets to make in the category in 2025, but they may be harder to find. As Bernstein, the Brightside COO notes, it will take deep thinking and research to find the pockets of opportunity where there isn’t a lot of established, well-capitalized competition. Not all venture firms and founders are willing to expend this level of effort, particularly those that only got excited about the category during the pandemic and are now focused on other shiny objects. But there are firms actively looking for the next generation to fund, like Health Velocity Capital, Khosla Ventures, 406 Ventures, 7wire Ventures, Thrive Capital, GreyMatter, Autism Impact Fund, Town Hall, and my very own Scrub Capital. The firms exploring the space today will need to “wrap their heads around evolving business models,” said Bernstein. “And there might also be a requirement of greater clinical and regulatory diligence.”

My prediction is the next big trend in this category will be “measurement based care,” which mental health startup Two Chairs is currently talking about in a big way, because we do need more data-driven tools to show whether or not a mental health intervention is working. And as I mentioned, very few companies are moving patients through varying levels of care. Someone might start out needing a psychiatrist, improve, and then only need a therapist. Or start with a therapist, but ultimately only need a daily interaction with a coach. That kind of triage might also be a job for AI, although there may be liability associated if it’s not done correctly and a patient doesn’t get the care they need. There’s also a lack of quality controls related to therapists, and a growing body of evidence (both studied and anecdotal) that indicates bad therapy may be worse than no therapy.

I believe technology will make the current set of businesses more efficient, thereby getting them to an exit. But I also perceive big challenges ahead related to payers. Those that can crack the health plan sale will have a massive edge. It’s hard to imagine doing that while also increasing utilization and not having solid evidence to back up that the intervention is driving long-term cost savings. Several payers I spoke with described feeling overwhelmed with the constant inbound from startups making very bold promises about their impact. Several health plan executives I spoke to on the condition of anonymity told me that they’ve lost some trust with companies in the category and they don’t have a clear sense of which companies are higher quality than others. Health plans want to see ROI. That’s possible, but challenging in behavioral health. Companies are being asked to prove cost reductions in an underwriting cycle of just 12 months, while clinical evidence might indicate that the true ROI comes from a longer and more sustained intervention. All of this is having an impact on behavioral health companies’ unit economics, including margin and year-over-year growth, because they are relying on network rates.

“Non-standard contracting is very hard right now,” said Jon Stout, a former investor with Optum Ventures and chief business officer at Motivo Health, which is focused on the opportunity in clinical supervision. “Five years ago, all the payers were considering a move to value-based, which would have been very good for the startups in the category, but there have been cuts to those teams.” Stout said that getting better contracts with payers is not impossible, but it’s like “moving mountains.”

Karan Singh, COO of Headspace, pointed to a future in which people can still access help on a daily basis, but through more innovative, AI-driven and scalable models – he referred to it as a “mental health companion.” To payers, that could represent thousands of dollars in cost savings, particularly when compared to several years of non-structured therapy without any clear outcomes. Singh believes there may also be a growing role for peer support, with companies like Marigold Health and Supportiv finding traction there. Nonprofits like Crisis Text Line are also finding that non-clinical peers can fill in the gaps and support each other, particularly when trained in providing validating, comforting conversation in moments of emotional hardship. There may not be a licensed clinical professional involved, but these interventions are known to work.

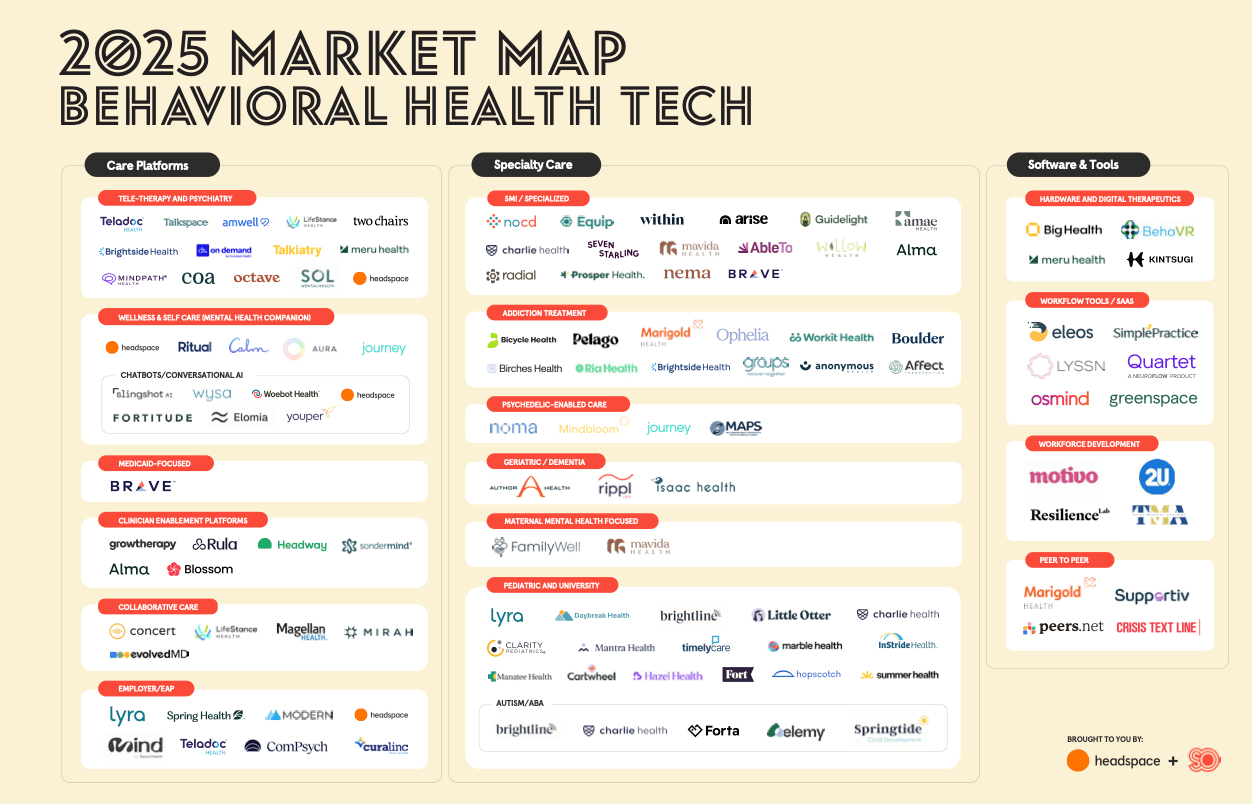

Despite all these very real and legitimate challenges, everyone I spoke to while researching this piece emphasized there are still big gaps in the market. To get a sense of those, take a look at the Headspace/ Second Opinion market map. Our map is not fully exhaustive, so if you’d like to add your company's name to our next edition, please feel free to do so here: [Link]. We plan to release a second edition in 2026.

Given that, Stout, who previously worked at AbleTo, believes the pendulum has swung too far. Plenty of companies are doing well, and there's a ton of white space for innovators. In a few years, there could be several IPOs that could light up enthusiasm in the space and bring back the fear of missing out (FOMO). And with FOMO comes higher valuations. 2025 could actually be the ideal time to invest while valuations are still reasonable, and with a lot more exit opportunities on the table.

I huddled with Jenna Glover, Headspace’s chief clinical officer, as well as Singh, its COO, about where we collectively see the biggest missed opportunities. We all noticed that companies in the severe mental illness category are really starting to have breakout success, such as Equip Health (eating disorders) and NOCD (OCD). There are big opportunities in the next few years for these companies to partner with those that focus on other modalities, levels of severity (lower and moderate acuity, versus high acuity), as well as other therapeutic areas.

We also see an opportunity for new players here. Glover and Singh noted that another benefit to getting into severe mental illness (SMI) is that payers will often pay far more up front to companies that can provide an alternative to far more expensive modalities, like residential treatment facilities. That is also attracting more investment, because margins tend to be higher for these businesses. We agreed that the biggest gaps are in conditions like bipolar, PTSD, and schizophrenia.

We found strikingly little activity in Medicaid, with Brave Health as a notable exception to the rule, as well as in companies that manage conditions or populations that may be considered more niche but are in fact a growing area of need. We found only a smattering of companies targeting geriatric populations, despite increasing reports of loneliness facing seniors (a health risk as deadly as smoking) and a growing aging population, as well as in maternal mental health (Family Well is a recent exception). We agreed that there’s ample opportunity in peer support and groups, because of the patient outcomes and favorable reimbursement rates, even though it’s highly operationally complex in practice.

Lastly, even as AI remains the focus of investors’ attention in 2025, we still feel there’s a massive opportunity to apply it to behavioral health. There are companies that offer conversational AI in the form of chatbots, including Headspace, but also plenty of opportunities to use the technology to improve the experience of scheduling appointments, or billing insurance, or compiling providers’ notes. Why does this matter? Historically, it’s been very hard for behavioral health companies to grow their revenues, deliver high-quality care, and keep providers happy. Because reimbursement has historically been so low, most companies have struggled to improve their margins and therefore gain further investment. This led to some very misaligned incentives and even some bad behavior to chase both margin and growth. Cerebral is a classic case study, as the company clearly favored prescribing medication, versus other ways of delivering care (dispensing medication tends to be much higher margin, versus, say, a one-on-one therapy appointment).

AI offers a way to scale the best providers, while also streamlining operations on the back-end. That could improve efficiency in multiple ways, so companies can focus on supporting their patients and ensuring that providers aren’t getting burned out.

“AI is the variable that could fundamentally change the unit economics for businesses in our space,” said Glover. “It’s going to change our ability to do better diagnosis, support our patients, and do that with a lot less margin.”

Bottom line: The herd mentality doesn’t usually result in great investments or world-changing ideas. Mental health may be a challenging area for a variety of reasons that we outlined in this piece, but it’s worth solving. Those that enter the space today will find that their natural allies are those who will remain in the space, during the highs and the lows, and will have an easier time avoiding the tourists or fair-weather friends. There’s still plenty of work to do, and the entrepreneurs that remain in the space may have scar tissue but also the skills required to get the job done, whether it’s the onerous licensure requirements, billing complexities, long sales cycles, or anything else. So let’s keep going.

Want to support Second Opinion?

🌟 Leave a review for the Second Opinion Podcast

📧 Share this email with other friends in the healthcare space!

💵 Become a paid subscriber!

📢 Become a sponsor