As women entering our late thirties (Chrissy) and early forties (Leslie), one of the big questions we’ve been grappling with lately is how menopause should be categorized. It’s a hectic life stage for most women due to family, work and caregiving responsibilities. And for some lucky women, light in terms of menopause symptoms. For others, it represents something closer to an experience of a disease, given the physiological changes that women experience and the fluctuations in hormones. While our physician readers may disagree with the “disease” terminology, most would agree that menopause brings with it some notable increases in health risks for women.

Why does this matter? Is it more than semantics? Diseases can be treated with medication, and in our country, there may also be billing codes associated with treatment. It also raises important questions that the life sciences world is only beginning to tackle, related to whether new drugs can be developed to delay menopause, not just to bring women more years of fertility, but also to slow down the aging process.

We’re committed to menopause as a big theme for the coming year - and we look forward to hearing your thoughts and comments about what we should be covering. Thanks to Found for making this edition of the newsletter free for all our subscribers!

This edition is sponsored by Found, a physician-designed weight care platform that has served more than 250,000 people with clinical care, medication, health coaching, habit tracking, and a supportive community.'

By Leah Rosenbaum

Around 6000 women go through menopause each day in the United States, and the global menopause market is expected to reach $24.4 billion by 2030. At Second Opinion, we’ve been writing for several years now about why menopause is finally becoming big business. And we see another sector on the rise in parallel.

GLP-1s are a breakthrough for a growing number of conditions, including obesity and cardiovascular disease. The estimated market size of these drugs ranges from $100 billion to $150 billion by 2030. We’ve been tracking the convergence of menopause and GLP-1s and believe this is only the beginning of how they will be viewed as a treatment for women during midlife. Potentially even as a women’s health drug.

Companies in women's health, particularly those focused on menopause or midlife, raised a combined $530 million between 2015 and 2023. The VC community is finally realizing that women in their midlife have spending power and a complex array of needs. Because, as we’ll argue, those needs don’t just include combating hot flashes or night sweats. It’s a much more complex picture than that, and that’s where the opportunities lie.

Rekha Kumar, MD, an endocrinology and metabolism specialist and head of medical affairs at Found — where more than 80% of members are women, with nearly half of that cohort at the typical age range of perimenopause or menopause — noted that women in midlife aren’t just experiencing perimenopause or menopause alone.

“They're coming in saying, ‘I think I'm having perimenopausal symptoms. I want HRT, I'm gaining weight,’” she said, “And you delve into it, and they're like, ‘well, I'm planning on being pregnant again in the next six months, or going through IVF.’ There is such a scientific and medical conflict there.”

So what does that include? Well, a dizzying number of symptoms, but also desires and needs that may even be in conflict. That’s why it’s crucial for providers not only to focus on the patient’s primary need but also to ask questions about the patient’s life goals. Is there a high degree of work-related stress? How about weight gain? Is that connected to menopause or something else? And also, the practical side, like what sort of activity and diet is possible within the constraints of their lives?

What’s intriguing to us is that for women with multiple goals or priorities, there are more treatment options than ever before. We have spoken to countless women from previous generations who described the entire midlife period as essentially one of suffering in silence. Nowadays, with the stigma around menopause starting to ease up, women are increasingly speaking up and getting treatment.

The impacts of GLP-1s during midlife

So what do those new treatment options look like?

Since many of the health conditions that women face in and around menopause are also caused by hormonal changes, it begs the question: Should GLP-1s be considered as a treatment for women’s health and hormone management beyond obesity? And what opportunities are there for the companies in the space that are already prescribing these medications?

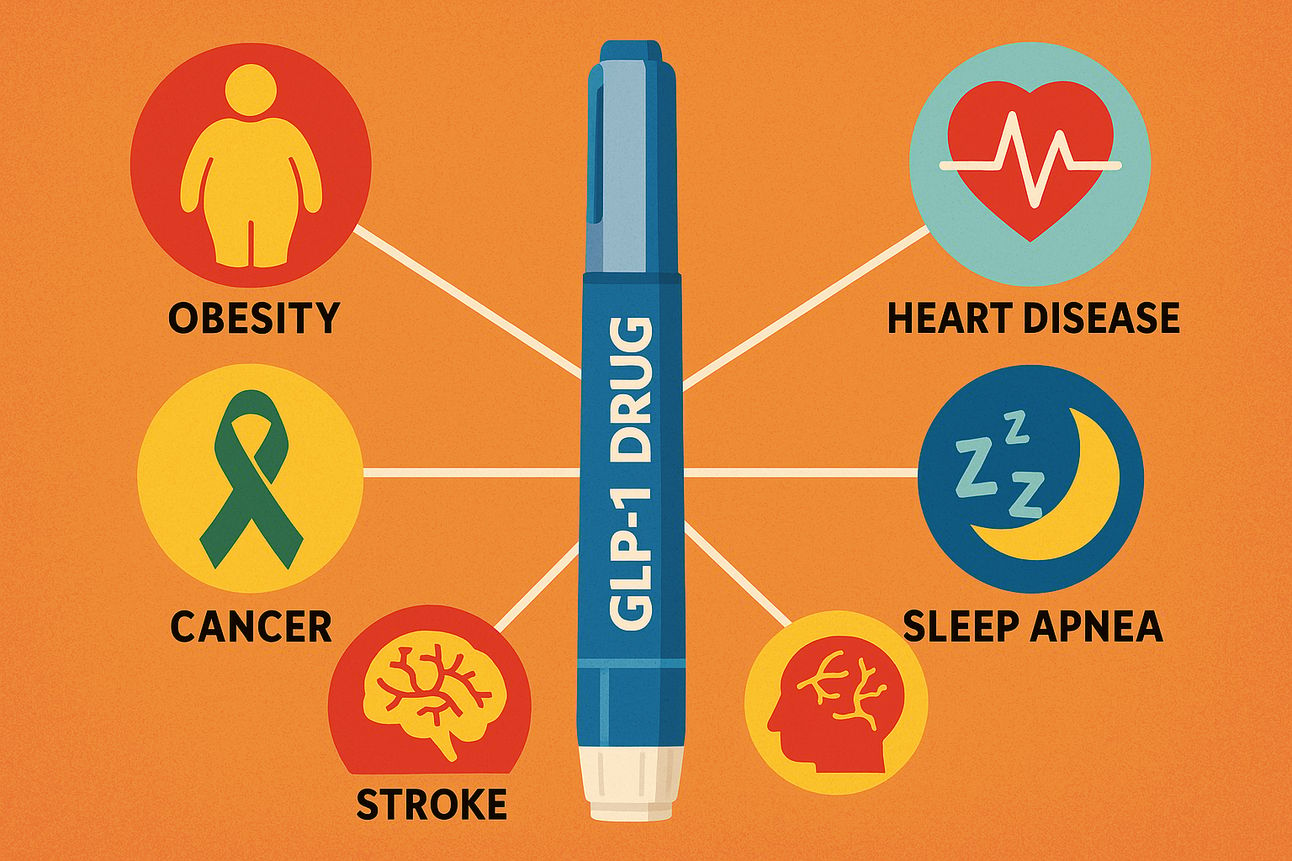

It wouldn’t be the first time GLP-1s surprised us. In addition to obesity, there is emerging evidence that GLP-1s are effective treatments for unexpected conditions, including cardiovascular disease, liver disease, Alzheimer’s disease, addiction, and binge eating.

Now we’re seeing preliminary evidence for GLP-1s as a women’s health drug to treat PCOS, and menopause-related weight gain, sometimes in conjunction with HRT medication. That, again, speaks to the need for platforms in women’s health, particularly allowing treatment of menopause and weight gain concurrently. There could be extremely strong linkages between the two. It may not be surprising that many of the companies prescribing GLP-1s also prescribe HRTs, and vice versa.

“GLP-1 receptor agonists may have an emerging role in managing some of the metabolic consequences of hormonal changes during this time of life, particularly weight gain, insulin resistance, and impaired glucose tolerance,” said Priya Jaisinghani, MD, an obesity medicine physician and endocrinologist based in New York.

Of course, GLP-1s aren’t the only treatment option. They might not even be the best one for every patient. Other treatment options, including hormone replacement therapy, strength training, and diet changes, may be enough for some menopause-related weight gain. Newly approved drugs, like Veozah, are targeted towards hot flashes specifically. Still, there is plenty of room for another class of drugs in this space, according to the experts we spoke with.

When we asked Dr. Kumar if she saw GLP-1s being used as a women’s health drug, she said that for that to happen, we need to change how we frame these medications’ indications. This gets back to a complex underlying question, related to how we categorize and even understand menopause. In today’s system, drug use is tied to a disease indication. But perimenopause and menopause aren’t considered diseases by the medical community — they are life stages. We believe that both could be true simultaneously.

As Dr. Kumar explained: “There will be a lot of off-label use, but we have to understand why we are using them in each particular case.”

Nisha Patel, MD, an internal medicine and obesity specialist based in San Francisco, also sees promise for GLP-1s in this broader arena of women’s health. She said they are “great tools for women across their lifespan,” except during pregnancy and breastfeeding, since there is no data on their use during those periods. She also mentioned a small study published last year that showed women who took the GLP-1 semaglutide while also taking hormone replacement therapy after menopause lost more weight than women who didn’t take hormone therapy. “It is an interesting association that I think needs to be looked into further,” Dr. Patel said.

It remains to be seen, however, if prescribing both together will become the standard of care.

We need more scientific evidence on several GLP-1 indications for women, including more rigorous studies on how GLP-1s affect fertility, PCOS, and menstrual cycles. With the funding cuts and uncertainty surrounding the Women’s Health Initiative’s future, we may not get there as quickly as we would like. Ideally, researchers would look into the interactions between hormone therapy and GLP-1s to see how these medications influence each other, and determine if hormone therapy is a way to further optimize GLP-1 use for perimenopausal and menopausal women.

We also need more research on GLP-1 side effects and how they impact women. We know that these drugs can cause some awful GI issues, nausea and vomiting among them, but it’s not known why some people get these side effects and why others don’t, or how to prevent them.

Will the shortages change GLP-1’s trajectory for women’s health?

We’re curious to know whether and how companies will continue to offer compounded GLP-1 medications now that the formulary shortage has been resolved. There could be future shortages because, as we noted, new possible indications for GLP-1s emerge weekly.

The rise in bespoke versions compounded with vitamins like B-12, intended to address the individualized needs of patients—such as supporting side effects—may be overshadowed by Eli Lilly’s recent lawsuit against Willow Health, Henry Meds, Mochi Health, and Fella Health. Whether this approach to personalization will continue to gain traction, or whether it will create a chilling effect across the industry remains to be seen. We don’t know the outcome, but we can’t wait to find out.